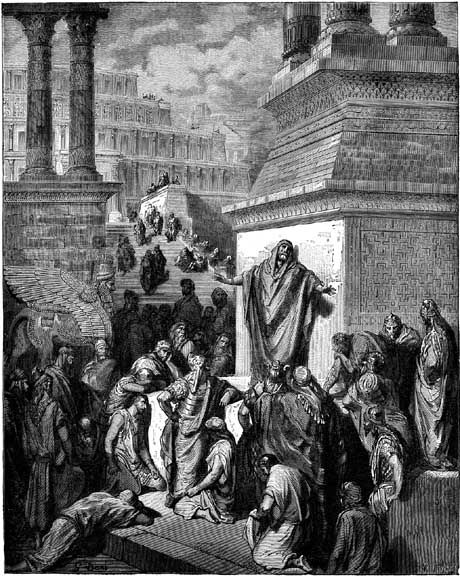

Jonah Warning Nineveh

When I began this short series I pointed out that, while we know little about Jonah, one thing we know is that Jonah was an insider and that the book was written by an insider for insiders. Today's insiders who read this short book are modern Christians and Jews. That is not to say that there is nothing to learn if you are not an insider. There is much for "outsiders" to learn, including much of that is painful for insiders to hear. Yet the lessons for insiders should be heeded by modern insiders because we are still not listening very well after 2700 years.

Unlike many of the wandering prophets we read about in the Bible, Jonah was very much an insider prophet, a prophet in service to the King and listened to by those in power. Jonah was a royal prophet. He was more powerful than a modern day bishop or church leader who is seldom listened to by the prevailing powers that be. But Jonah had credentials that only a prophet in a theocracy sitting near the throne of power could have.

And, to top that off, he was first and foremost, a prophet of God. He was God's ultimate insider, set apart for the sole duty of being the mouthpiece for God. As God's prophet he had God's ear and was God's personal spokesman. When he started an oracle with, "Thus says the Lord," people listened. People in power who could make God's wishes happen if they heeded Jonah listened.

But Jonah comes off very poorly in this book. He is hardly the prophet that God would have him be. He is vain, disobedient, stubborn, self centered, self righteous, arrogant and bitter. And, ironically, in this book it is not Jonah, the insider, who comes off well in our eyes, but the outsiders. It is the outsiders who look good to us, and, in the end, they also look good to God.

There are two groups of insiders highlighted in the story: first, the sailors and their captain; and, second, the Ninevites and their king.

I imagine that the sailors were a rugged bunch of individuals, having little sociologically in common with one another, coming from different places, worshiping different gods, trying to make a living in a dangerous occupation. That is one thing they have in common: a dangerous, difficult, hard, low paying vocation.

And they all know the sea and respect the danger of a storm at sea. When one comes they know what they must do: they pray to their individual gods and then they take action. They are none of them Israelites, the "people of God" that Jonah is familiar with. Like the Ninevites they represent the people of "the world," far from the "people of God," purely outsiders, and worse, pagans, worshiping other gods.

To Jonah all of these outsiders, sailors and Ninevites, are anathema.

But the major purpose of the Book of Jonah is to shock insiders into seeing that these outsiders are people who do the things that insiders are supposed to do, and often do not actually do. They exhibit characteristics that insiders associate only with other insiders, as if moral values and an awareness of God were a monopoly owned by insiders.

The sailors are humane. They risk their lives trying to row the boat to shore and to save the ship and Jonah. They are pious. When faced with danger they turn first to prayer and then to action. They are practical. When disaster strikes they work, shoulder to shoulder, together, to do what they can. They do not easily give up.

And, they are open to theological growth! When, at the height of the storm they learn about the true God from Jonah, unlike Jonah, they pray to his God and offer to Him their sacrifices. Meanwhile, Jonah, the prophet of this God, sleeps and does not take the time to pray to the God he claims to worship.

Jonah is willing to tell them about his God, but it does not occur to Jonah to pray to God even during the height of the storm. He doesn't even pray on his own behalf, and certainly utters not a word on theirs.

The story wants insiders to be very uncomfortable. We insiders are supposed to identify with Jonah, a fellow insider. But we have a deeper sense of what is right and we know that we actually identify with the outsiders. We want to think that we would act like the outsiders, not like Jonah.

What is happening here is that the writer wants insiders, those of us who see ourselves as "God's people," to reevaluate our attitudes and prejudices toward "outsiders," those that we would never normally see as "people of God." Perhaps it might help us to remember that centuries later St. John would write: "For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son..." John did not write, "For God so loved insiders...."

Turning to Nineveh, we see the Israelites calling her a whore of a city. Jonah hated Nineveh with all his passion, yet there is no indication that, up to now, Jonah had ever set foot in it. But, spit safely onto the beach by the whale, Jonah is given by God a second chance to go to Nineveh and see for himself. And this time, with great reluctance, Jonah goes to the whore, Nineveh.

And, miracles of miracles, he preaches the imminent destruction of the city and the whore listens! And the murderous King of Nineveh hears and takes action. The Ninevites respond with mourning. The King himself sits in sack cloth and ashes. He calls for a fast, one extending to even the animals as well as the people. And the irony is that even the King has no clue whether any of this will help and avoid the destruction of the city by God.

One of the great ironic statements in the Bible or in any other literature, is the King's "Who knows? God may relent and change His mind; He may turn from His fierce anger, so that we do not perish."

The King does not presume to know if God will have mercy and turn from his righteous wrath. This outsider, this leader of the city known as the whore, throws himself and his city on the mercy of God. He knows all too well of the sins of his city, but, like the captain of the ship, his overriding concern is for the salvation of his people. And he intuits what Jonah claims to know and even once prayed, "Deliverance belongs to the Lord."

And the city is "overthrown" all right. But not as Jonah expected. God changes his mind and does not consume it with His wrath. It is overthrown by the repentance of its people, and by the love of God for these lowly "outsiders." They are precious in God's sight.

Who besides the Ninevites care that God repents of his righteous anger? Certainly Jonah, this prophet of God, cares, but he does not see this as a good thing. Rather he is enraged. And he walks out of the city, turning his back on this miracle of repentance and love. He tells himself that God should have destroyed this city of whoredom, which by every standard of justice, and yes, vengeance, should be destroyed.

Jonah, this prophet of God, this insider of insiders, hated what happened to the city and he was furious with God. He hated that the God to whom he sang while in the belly of the fish, "Deliverance belongs to the Lord," would have the nerve to deliver THEM!

This story insists that insiders, those of us within our churches and synagogues, who think of ourselves as God's "own" people, reevaluate how we feel about and act toward all of those "outsiders" we hold morally inferior to us. It is past time that we recognize that God cares about and loves all the peoples of the world, not just Christians and Jews.

This story speaks a sharp word of criticism against a people who prefer the safety of their own groups. It calls them to be about the tasks to which God calls them. It warns insiders against the danger of forgetting that we are ambassadors, givers, healers, friends and neighbors, participating in reconciling the world to God.

To me this story says that we who think of ourselves as "insiders" must, in our lives and by our actions, open ourselves to serve and to love all others, in a world filled with "outsiders." And then, "Who knows?" Perhaps God might spare US a thought, and be pleased by the compassion of those who claim to be His people.

Monte