This is the 5th of a series of essays that cover the origin of the Israelite nation and conclude with a discussion of the Ten Commandments.

Prior essays are

http://open.salon.com/blog/monte_canfield/2009/10/19/birth_of_the_israelite_nation

http://open.salon.com/blog/monte_canfield/2009/10/20/torah_instruction_for_living

http://open.salon.com/blog/monte_canfield/2009/10/21/manna_bread_for_life_but_is_it_enough

http://open.salon.com/blog/monte_canfield/2009/10/22/testing_god

This will, in some ways, be the most difficult essay to understand of this series. But it will answer questions about the Bible that too many in the past have forgotten to ask; which has led to the misuse of Scripture to further not theological but ideological goals.

The Ten Commandments are also known as The Decalogue, a word worth knowing. We are now at Chapter 19 of Exodus. The Decalogue comes in Chapter 20.

But, unless we understand why and how we came to have the Decalogue we will miss much of what God is telling us; and, we can fall into the common Christian trap of taking the Commandments out of context and missing their true meaning. We want to avoid doing that. You can't truly understand any Biblical text without understanding the context in which it is written.

We come now to a point in our story that is absolutely critical to our understanding of who Jews and Christians are as people of faith: the formation of the nation of Israel.

Up to now the people had been led by and protected by Yahweh, but they claimed no special allegiance to him; and he made no universal demands on them.

In fact, when they complained it was usually to and about Moses, not God. Moses knew that when they complained against him they were really complaining about God. But the people did not quickly realize that to be the case, as the incident of the Water from the Rock showed us.

Yet, increasingly, they had begun to realize that Moses had no power except that which God gave him, and they were more and more turning to Moses not to provide his counsel, but to seek God's counsel through Moses.

God had tested the people in several specific ways, such as how they were to treat the manna he provided. Now a bigger decision will be made by God: he will decide to keep them as his own chosen people through whom he will seek to bless the nations of the world. That will be a monumental task, one at which they would sometimes succeed, but one at which they, like all humans, would often fail.

So Chapter 19, at the very heart of the Book of Exodus, is where God does make universal demands upon the people; and where they commit themselves wholly to God. By agreeing to become God's "priestly kingdom and a holy nation," they become partners in the covenant between God and Abraham.

This "new covenant" will be known as the "Mosaic Covenant," the "Covenant with Moses." It is more than its name for it is a covenant not only between God and Moses but between God and this chosen people. And it is really an extension of the larger covenant that God made with Abraham.

At its core what this covenant between God and the Israelites does is expand upon the covenant with Abraham to include an entire people, many of who bear no known direct relationship to Abraham, but who now form an elected, redeemed, believing, worshiping community.

In a similar way, Christians, who also have no known direct blood relationship to Abraham, will much later be called by another Jew whom Christians know as St. Peter, "...A chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his possession...." (1 Peter 2;9) Christians see themselves as descendants of this covenant because of the "New Covenant" which we entered through the blood of our Jewish Messiah, Jesus of Nazareth.

While this Mosaic covenant is really not new in its intent, this is truly a "new" covenant for those involved in it, those whom we call Israelites; a covenant made with a people who were held in slavery for over 400 years, a bunch of refugees, for whom the promises made by God to Abraham were but the dim recollections of a clouded history. For them it would be the beginning of a whole new way of life under God.

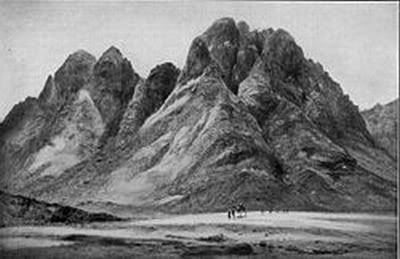

All of the covenant making, the giving of the Ten Commandments, and the expansion of the law in the "Covenant Code" which follows the Decalogue and details instructions on how those people were to live, as well as the establishment of all of the fundamental rituals of worship, the construction of the tabernacle, the ark of the covenant and all the related fixtures of worship: all of this takes place at the foot of Mr. Sinai.

Everything that happens in the rest of Exodus, in all of Leviticus, and in the first ten chapters of Numbers, all of it, happens at the Holy Mountain, where the people camp for just under one year. And all of it is further summarized in the Book of Deuteronomy.

In the Book of Exodus, what happens in Chapter 19 lays the foundation for everything that will follow in the rest of the Bible, both in the Old and the New Testaments. The section of text, the pericope, starting at chapter 19 through Chapter 24, informs forever the Israelite experience.

It is here where God offers His covenant with the people and demands obedience. It is here where the people respond positively. It is here where the Torah, the instructions for life under God, is promulgated. It is here where God shows himself to the people, and speaks directly to them, issuing the Ten Commandments, which are the foundation of the "Law", or Torah.

It is here where the people, fearful of further direct contact with Yahweh, seek Moses as an intermediary between them and this Almighty God. It is here where the "Covenant Code," that long list of detailed rules for day-to-day living, is given to the people; and, finally, it is here where God once more appears to the leaders of the people, and where the Covenant is completed. In other words, it is here that Israel is born. And, in a very real sense, it is here where the faith of modern Jews and Christians begins.

When we look at the critical first verses of Chapter 19, the first thing that we notice is that the first two verses repeat the obvious: That the Israelites came to the wilderness of Sinai about two months after they left Egypt, coming from Rephidim, and camped in the wilderness. Now they camp at the foot of the Holy Mountain, which we call today, Mt. Sinai, but was then more often called Mt. Horeb.

I am going to use this obvious repetition here at the beginning of Chapter 19 as a reason for us to take a side trip for the rest of this essay.

This side trip could have been taken earlier, but I wanted to wait until we were at a crucial point in the text. We need to understand how this part of the Bible was put together, so you'll begin to understand why the Bible often repeats itself, and sometimes even contradicts itself.

This repetition is obvious in the first five books of the Old Testament, which are called the "Pentateuch," (literally, "Five Books"), although it is readily apparent in other parts of the Old Testament and also in parts of the New Testament as well. In the Old Testament, for example, the 10 Commandments appear twice, not once, in Exodus and again in Deuteronomy. And the Commandments are not exactly the same in both places. (Deuteronomy translates roughly: "the second telling." That book is written as a series of speeches by Moses to the people prior to entering the Promised Land.)

In the case of Exodus and all of the Pentateuch and in many subsequent chapters of the Old Testament, you will find a lot of this overlapping repetition and the taking of different slants on the same event. This is because these books are an edited accumulation of at least four separate text streams. They were "redacted," that is cut and pasted together, and bound into a text with transitional words by the "redactor."

The sources of these words come from the different traditions of different groups of Israelites, and were gathered over a period of hundreds of years. They were first passed along by word of mouth, and only much later were they written down.

The four most obvious text sources in the Old Testament are called J, E, P and D.

"J" stands for "Yahwist," meaning that in that source God is called Yahweh. The "J" comes from the German spelling of Yahweh, which is "Jahweh." The J source is believed to come from*the traditions of the Southern tribes of Israel.

[ * When I say "believed to come from" I do not mean it is just a guess. Conclusions as to these source streams come after decades of careful analysis of the words, the forms of the language and careful and laborious study of the text.]

The "E" strand of tradition stands for "Eloist," because, in these sections of text, God is called "El" or "El-ohim," or some other variation of "El," which is translated as "God." The E source is believed to stem from the traditions of the Northern tribes of Israel.

The "P" source stands for the "Priestly" writer or editor. We do not know if it was a single editor, although that is how it is usually discussed. Likely there were multiple writers who worked together on these complicated texts.

This source is primarily responsible for all the information and details about building the tabernacle, the forms of ritual and ceremony, and other details of sacrifice and worship. In other words, this source is interested in the way the people are to worship of God. A huge part of the first five books of the Bible is devoted to this.

"D" stands for "Deuteronomist" and, in many ways this is the most important textual source of all. In addition to adding textual material to the Bible, it was the Deuteronomist who pulled all of the threads together. This source came hundreds of years after "J" and "E" and comes from the same writer, or writers, who compiled the Book of Deuteronomy.

Although the source is likely composed of a school of writers, this source is called often called simply the "Deuteronomistic Historian" because the writers' strong interest in getting a clear understanding of what actually happened to the Israelites from the time they left Egypt.

This interest continues through not only the Pentateuch but also through the books that follow. The Deuteronomistic History of the Bible runs all the way to the end of Second Kings. Thus, much of the heart of what we know as the Hebrew Bible, or Old Testament, was gathered together by this writer or group of writers.

The final form of the Bible that we see today is called the "canon," or "canonical" text. It is the text accepted by Jews and Christians who are members of the worshiping community as the authentic, sanctified record of God's relationship to us. It is this text that is "normative" for us: that is, it is the text from which we base our actions on how to live under God's leadership.

The "canonical text" of the Old Testament is the final result of many redactions over literally hundreds of years. And the New Testament underwent similar, but not as complete, redactions as well.

The final editors had to accommodate many different ideas, stories, and theological positions. That it is as coherent as it is seems to me truly amazing. So, as we read the Bible we need to keep in mind that the Bible is not a book written by one person at one time for one reason. Rather it is a beautiful tapestry, a quilt, woven over centuries.

As such we must try not to get hung up on the little inconsistencies, or the repetitions, or the lack of historical sequence in some of the chapters. It is important to remember that the Bible is primarily theology, not history; It is God's revelation of God's self to us.

Remember also that the so-called "history" in Bible comes to us through many different sets of eyes. Believers must evaluate the Bible through the eyes of faith. It is not science. Nor is it written as it would be written by a modern day historian. If you subject it to the tests of modern science or history writing, then you have simply missed God's purpose in giving us this documentation of God's relationship to us. It is to be judged by God's standards, not ours.

Just as we learn when looking at the gospel accounts of the death and resurrection of Jesus, different communities of faith often saw the same events slightly differently, saw some events that the other groups did not see at all, and reported all the events a little differently, one from the other.

But Jews and Christians believe that God guided the hearts and hands of those who wrote and edited these words. In other words, we believe that they were inspired by God.

Most conservative Christians also believe that the Bible as we have it today is also infallible and inerrant, even though wholly translated from texts written long after the events depicted, and even though no original manuscripts exist to our knowledge. Nevertheless, these Christians believe that these words are to be taken literally.

I do not think that position is tenable. It is based on assumptions long ago proven to be unsubstantiated. But each reader of the texts that make up the Bible must make that decision for him or her self.

One final thought on this. The canonical text of the Bible is often called "The Word of God." While I understand why that is said, I believe that to be wrong and I do not think it is just semantics when I say that. It is far too easy to say that and become so enamored with the Book that we forget that it is the Witness to God. It is not God.

The Bible stands as witness and contains many words of God to us. But we must never fall into Bibliolatry. We do not worship a book. We worship God. And there is a big difference. The Bible was written within, and is addressed to, the worshiping community. But God is still speaking to us and we must evaluate the words of the Bible in the context of the worshiping community today.

The Bible is both spoken to us and interpreted by the worshiping community. What may have been seen as acceptable interpretation of certain texts in the Bible in one generation or century may well not be acceptable to the worshiping community in a later generation or century in the light of a different understanding of how the Bible speaks to that later generation.

The Bible does not and cannot stand alone, isolated, out of the context of its intended audience. The traditions of the worshiping community and the experiences of that community today must be taken into account when deciding how God would have us live, and how we are to interpret what the Bible means for us today.

And so, while the Bible is ancient and honored, it is not to be confused with the whole truth that God has to reveal to us. Each generation of the faith community must read and understand the Bible within the context in which we find ourselves. In other words the Bible is, and has always been, a Living Bible.

We need to work to keep it as such and not become obsessed with anachronistic teaching which makes no sense for a current generation of believers.

Next: God calls Moses to take a message to the people! That message, and their response, will change everything!

God bless.