First Published in Open Salon, MARCH 5, 2010 2:36PM

NOTE TO READERS: This Lenten essay was originally published on Open Salon, February 25, 2009. It is part of my Christian Calendar Series. It is intended to set a tone for thinking about the season of Lent. I have edited it for 2010, clarifying certain points and improving the flow of the text.

Christian liturgy, ritual and most of Christian theology change little from year to year. The reason for the Christian Calendar is to encourage Christians to rehearse, ponder and reflect on, year after year, the life, death and resurrection of Jesus, the Christ, so that His life becomes part and parcel of our family history.

The story of Christ changes little, but we, His disciple, change and grow, become ill, or face death, our own or a loved one's, and in so doing we come each year to view the events of Christ and the traditions of His Church through different eyes.

Hopefully, what I write in this series will have a certain timelessness, updated slightly each year to improve clarity and thereby open more deeply our understanding of aspects of the events celebrated during the Christian Year.

This Lenten essay for 2010 lays out some basic parameters of orthodox Christian belief. What is written here are my own beliefs, which are widely shared by Christians in most mainline Protestant denominations and in the Roman and Orthodox Catholic denominations in the United States as being fundamental to Christian faith.

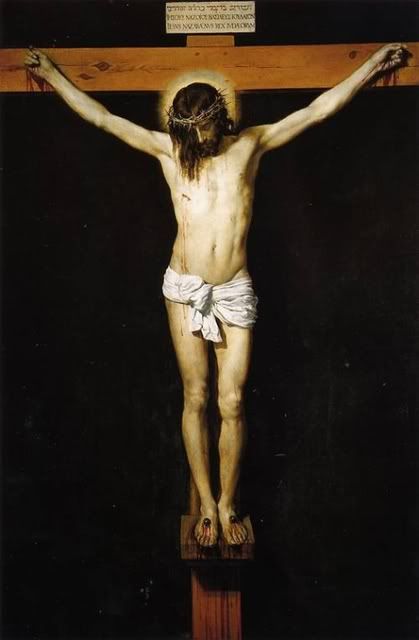

The Death of the Messiah: Introduction

This is a Christian Reflection, written for other Christians, other people of faith who may wish to better understand this aspect of Christianity, and for others, seekers and the curious, who may wish to know about the Christian understanding of the events leading up to the crucifixion of Jesus, the Christ. The Reflection is a statement of belief. It is kerygma, proclamation. If you come here with an open heart and an intention to be tolerant of the beliefs of others, all beliefs, all religions, or none at all, you are in the right place. If not, this post is not for you.

"How Do You See the Death of the Messiah?"

This is the first of a series of four Lenten Reflections on the Death of the Messiah, in other words, on the Passion of Jesus, the Christ. The series is the result of research I did to help ordinary Christians better understand the meaning of the Death of Jesus.

It is my conviction that our understanding of Christ's Passion has been warped badly by well meaning scholars and pastors who have sought to simplify the reality of His death. Simplification is often a good thing. But when simplification leads to confusion and false understandings of what the Bible says, then it ceases to be useful.

I feel strongly that we need to understand the Cross of Christ as God has taught it, not as we might like to hear it. Therefore, four times during Lent, with our focus clearly on the death of Jesus on Good Friday, we will look at the events immediately preceding Jesus' death and at his crucifixion. This Reflection and the next constitute an overview of all four Gospel accounts of the death of Jesus.

The final two Reflections will be a more detailed look at two of the four accounts, those of Mark and Luke. We will not look at Matthew and John in that detail; but the contrasts between Mark and Luke are clear enough that you will be able to understand that, like these two Gospel accounts, Matthew and John are also different in their understanding of the Passion.

Teachng Reflections like these demand more of you than a little skim of the text. You will need to read rather carefully so that you can form your own opinions as to what is meant. In fact, contrary to many well meaning, but misled people, there are seldom simple answers, including in the Bible.

Jesus’ death was not simple. But his death, when viewed in the light of his subsequent resurrection, is the most important event in Christian faith. Christian salvation literally depends on it. And so Christians certainly need to understand it. Most importantly, Christians need to understand what the Bible says about it, not what we might have heard that it says, or what we might wish that it says.

So I am inviting you to a true Lenten “discipline,” in the best sense of that word. And I promise you that if you will pay attention the reward will be great, for you will have a far better grasp on this event that Christians believe is the pivotal event in human history.

I chose the series title, The Death of the Messiah, in honor of the magnificent, unparalleled, work of the same name be Fr. Raymond Brown. His book, The Death of the Messiah is universally recognized as the most significant contribution to understanding the death of Jesus in the history of the church. That monumental work is over 1800 pages long. Obviously, we can only glean the highlights in a short series of reflections, but I need to acknowledge that Raymond Brown has greatly influenced my own thinking on this issue.

We will be looking at a very small segment of the Bible: the passion and crucifixion of Jesus, through four very different sets of eyes: those of Mark, Matthew, Luke and John. What we probably don't realize, however, is that most of us have created yet a fifth set of eyes. This fifth set of eyes is the one by which we have filtered what we know from those four very different accounts into one homogenous account that we believe fits what happened to Jesus in the brief time from Gethesemane to the grave.

We may even think that all four Gospel accounts of the death of the Messiah are essentially the same, and that our understanding of what happened to Jesus and how he approached his death is based on one uniform account. But that is not true.

The accounts of his death are not the same in key ways; and the Jesus depicted in each of those accounts is quite different from the others. The four gospels vary substantially, both as to what the Gospel writers say happened, and as to the theological implications and conclusions that each individual writer gives to the story.

For some that may be jarring, disquieting, and they may not even want to hear it. Christians naturally want to "harmonize" the four Gospel accounts, make them into a homogenous unit, with no loose ends. Attempts at "harmonizing the Gospels" have been made from the beginning of Christianity. None have been successful.

When we seek to harmonize the gospel accounts then we fall victim to believing what we want to believe rather than what the Bible clearly tells us. We, quite naturally, I think, would prefer one set of so-called "facts" to the rather differing narratives we read in the Bible.

We are like a good detective called to take the statements of four witnesses to an accident at an intersection, each standing at very different places, and while all saw the same thing, none of the four eye witnesses agree on what they saw.

The early church struggled with this problem for many years. But, and this is very important, the church, from the beginning, believed that the divinely revealed scriptures, even while often differing in detail, were the work of God, processed through the minds and hands of man, yes, but nevertheless divinely inspired by God.

And, for over 1600 years, the church has said that, regardless of their lack of harmony, the four Gospel accounts of Jesus were intended to give us different pictures of Jesus; and that, therefore, all were true in the eyes of faith. The church has consistently held that no one account of his life, death and resurrection could capture all the facets of his life and death.

Therefore, while many individuals have tried to harmonize the Gospels through the centuries, the church has seldom encouraged these attempts, which is precisely why we have four Gospels and not one. The church has been far more content than most individuals to allow the Gospels to stand as they are, seeing them as four different, divinely inspired ways of viewing the same events.

And that is the tack we shall take in this series. The truth is that the Gospels, and the death of Jesus as reported in them, cannot be harmonized. They are different, both in substance and in theological outlook. For instance, the Jesus described in Matthew and Mark is a far different Jesus than the one described in John, in almost every way imaginable.

Now, if you are a believer in Christ you have two choices. You can say that they all cannot be true and insist on harmonizing them, force fitting them into your own pre-conceived ideas of what you think went on, or at least what you think should have gone on.

Or, you can look at the Gospels as they stand and see what God is trying to tell us about the death of Jesus through the divinely inspired work of these four stories. Fr. Raymond Brown decided to do the latter: to look at each Gospel separately and to then attempt to discern God's message from the differing texts. That is what I shall be doing in this series, using Dr. Brown as our guide.

What we shall find when we are finished is that Jesus was and is a far more complicated being than we previously thought; and that the writers of the Gospels had to struggle with that fact. And they also had to struggle with the fact that they wrote long after the event took place.

Jesus died about 30 AD. The earliest Gospel, Mark, was written at least some 20 to 30 years later but, most likely, about 40 years later, around 70 AD. Luke was likely written about the mid-80s AD, over 50 years after the death of Christ. Matthew was probably written sometime between 80 and 100 AD, 50 to 70 years after the death of Jesus.

The date of the writing of the Gospel according to John is harder to pin down, but, in any case was not before 75 AD or much later than 100 AD, that is, 45 to 70 years after the death of the Messiah. In other words, if they were writing today, they would be writing about something that happened somewhere between 1910 and 1980!

There was no intention to write the Gospels immediately after Jesus died. The whole point of writing the Gospels at all was that Jesus did not return as quickly as expected and the stories were starting to get confused, sometimes deliberately, as they were verbally passed down year after year.

The original eye-witnesses were dying off, or already dead. Many false oral gospels were springing up in the widely dispersed church. Luke makes this most clear in the preface to his Gospel where he tells us that he is writing it to set the record straight.

Each of the four gospels in the Bible was intended for the Christian community in which the writer resided. There is no evidence that the writer thought that he was writing to the church universal.

Each writer's resources were slightly different. Mark, the earliest written, wrote primarily from the oral tradition, that is, from the verbal stories of Jesus told in his community by its leaders. There is no evidence that he had any written materials to edit, although that is possible.

Matthew, writing quite a bit later, relied heavily on Mark's gospel, often word for word. It is clear that Matthew edited and adapted from Mark. But he wrote a much longer Gospel, adding items from his own tradition, the oral tradition in his community and from other sources.

Matthew also added early Christian "apologetics", in other words, defenses of the faith made by early church leaders against accusations and threats from the Jewish leaders and the Romans. He adds, for instance, scenes about the death of Judas, about Pilate washing his hands of the whole affair, about the dream of Pilate's wife, and he places guards at the tomb.

Both Matthew and Luke seem to have shared ideas from a written source that we no longer have any record of. That source is simply called "Q" for the German word, "quelle" which means "source" in English. We know this because both Matthew and Luke have identical word for word accounts in their Gospels that are unknown to Mark or John. In addition, both Matthew and Luke drew from their own oral, and perhaps partially written, traditions.

John's Gospel is radically different than the others, so different that while the other three are called "synoptic," that is, they can be "viewed together," John's is called simply "the fourth Gospel." There is no evidence that John relied on any of the other three Gospels in the composition of his Gospel, although it is likely that he had access to Mark's and, perhaps, the other two as well.

But John, even more than the other three Gospel writers, was consciously and very intentionally writing a theology of the Christ, and his emphasis is on discerning who Jesus was, what Jesus' relationship to the Father was, and on what Jesus said and tried to teach us as that relates to God's intention for Jesus here on earth.

Jesus' ministry in John is three years long, not one or one and a half as in the other Gospels; three Passover feasts are celebrated during his ministry, not one, and he makes three trips between Galilee and Jerusalem, not one. In fact, in John most of Jesus' ministry is said to be concentrated in Judea and Jerusalem, not in Galilee as in the other Gospels.

The chronology of the trial and crucifixion is quite different as well, including saying that the Friday of the crucifixion was not the Passover, but the day of Preparation for Passover, thus John has no Passover meal in the upper room (which becomes the first Eucharist in the other Gospels), but rather an ordinary supper after which he washes the feet of the disciples and proceeds to make several lengthy speeches to the disciples, speeches the other Gospels know nothing about. And there are many other differences about the last days of Jesus in John's Gospel.

But, as different as these Gospel narratives are, we must be clear about one vitally important truth that people, particularly critics of the Gospels, do not seem to understand. None of the Gospel writers was trying to write history. All were writing documents of faith, kerygma, proclamation, filtered through the eyes of faith. They were writing theology, not history.

History as we know it today, based on careful gathering of the physical facts, was not on the agenda of these writers. History writing as we know it was simply unknown to the writers of the Gospels. They wrote to tell us the Good News of Jesus, not to nail down the precise facts of his life.

Theirs was a labor of love, of revelation, of faith. They were not trying to write a nice text book that could be adopted for use in a college history course. Please try to get that fact into your understanding. It will save you enormous heartburn in the future.

So, where does this leave us? Well, if you believe as I do, that the Bible is not just another book; that it is something more than, say, the writings of Shakespeare, or Plato, or Martin Luther; if you believe that the writers of the Bible were divinely inspired, anointed by the Holy Spirit, as I do, to write what they wrote, then, with me, you must conclude that the differences in the four Gospel accounts of the death of the Messiah were intentional. And the differences will, I believe, never be reconciled by us, or by anyone else.

I believe that God gave us four Gospels, not one, on purpose. And I believe s/he expects us to read all four of them and to learn from them, content to let them be for us what they are: divinely inspired books for educating us about the great mystery that is our God, and about his/her Son, Jesus Christ.

We will, later in this series, explore two of these Gospel accounts in some detail. We will note some of the places where the Gospels do not agree on the details. Where that is the case we will try to see if we can determine why that is, or if it makes any difference at all.

But that will not be, and should not be, the primary focus of this Lenten series. The primary focus will be to allow us to see the Jesus that each writer saw, the Jesus that the Holy Spirit inspired them to write about, the Jesus that we need to know, but, in Philip Yancey's term, who, in fact, may be "the Jesus we never knew".

The next Reflection will spend some time looking at why it is good that we have four different portrayals of the death of the Messiah.

God bless you all.

Monte