NOTE TO READERS: This Lenten essay was originally published on Open Salon, March 5, 2009. It is part of my Christian Calendar Series. I have edited it for 2010, clarifying certain points and improving the flow of the text.

Christian liturgy, ritual and most of Christian theology change little from year to year. The reason for the Christian Calendar is to encourage Christians to rehearse, ponder and reflect on, year after year, the life, death and resurrection of Jesus, the Christ, so that His life becomes part and parcel of our family history.The story of Christ changes little, but we, His disciple, change and grow, become ill, or face death, our own or a loved one's, and in so doing we come each year to view the events of Christ and the traditions of His Church through different eyes.

Hopefully, what I write in this series will have a certain timelessness, updated slightly each year to improve clarity and thereby open more deeply our understanding of aspects of the events celebrated during the Christian Year.

This Lenten essay for 2010 lays out some basic parameters of orthodox Christian belief. What is written here are my own beliefs, which are widely shared by Christians in most mainline Protestant denominations and in the Roman and Orthodox Catholic denominations in the United States as being fundamental to Christian faith.

Note: Part One of The Death of the Messiah, 2010 Edition can be found here: ttp://open.salon.com/blog/monte_canfield/2010/03/05/the_death_of_the_messiah_introduction_for_lent_2010

Why it is Good to have Four Different Views

of The Death of The Messiah

Overview:

Last Friday in Part One I introduced this series, edited for 2010, on The Death of the Messiah. I pointed out that, while we may think there is only one story of the death of the Messiah, repeated four times, in fact there are four different renditions of the story of Jesus' death, both in the details and in the portrait of Jesus presented. I also said that there is also a fifth rendition: the one that we create from the other four.

I noted that from the perspective of the Christian believer these Gospel stories were divinely inspired and that God was therefore, both mindful of the inconsistencies in the stories, and intentional in his inspiration, in that he wants us to be able to see Jesus' death from four unique vantage points.

We do not improve on the Gospel accounts by trying to harmonize them, regardless how tempting it is to try to do so. Ultimately, all attempts at harmonizing the Gospels never give a true picture of what God is saying to us in those sacred texts.

Therefore, I ended Part One telling you that having four differing stories was a good thing, in spite of the ulcers that it must give to those who want all of the stories of Jesus to be clear, concise, neat and without factual disagreement.

Part of the problem for such people is that they insist on viewing the Gospels as history, which they are not. They are theology told in narratives, stories, and are kerygma, proclamation. Mostly they are proclamations of the Good News (Gospel) of Jesus the Christ.

Part Two:

While our vanity makes this hard to comprehend, Christians should understand that the stories in the Bible are not written to meet any human standard. They only meet the standard that God wanted them to meet when s/he inspired the writers of the Gospels to write them, a standard which God has not felt it necessary to justify to us. I'm comfortable with that, since s/he is God and I am not.

But many are not comfortable with that at all, and have, unsuccessfully, tried to "harmonize" the Gospels, doing away with troublesome inconsistencies. We are not going to do that. In fact, we're going to look at a couple of those inconsistencies today, and then use them to make the point that it is a good thing that we have four differing accounts of the Death of the Messiah.

First, let's look at the Gospel narratives in general. If you think about it logically, the first thing you will notice is that all the Gospels do hold to a common, basic outline of the events leading to the crucifixion. And that makes perfect sense. After all, there was a basic order of events that took place, indeed, had to take place, and each of the Gospel writers had to take this into account.

Thus, Jesus' arrest had to precede his trial, and the trial had to precede the sentence, and the sentence had to precede His execution. And all the Gospels contain these elements. In other words, all share a common plot. And that is just what it is: a plot of a drama, one we call "The Death of the Messiah."

And, in this narrative, this drama, there are not only the actions and reactions of Jesus, but also of supporting characters, like Peter and Judas and Pilate. And the drama is heightened by the contrasts between these characters: innocent Jesus and guilty Barabbas, faithful Jesus and betraying Peter, and in one of the Gospels, wise and troubled Pilate versus vile and remorseless "Jews". Even the scoffing Jewish leaders have their antitheses in the Roman soldier who, in two accounts, declares Jesus to be, in fact, the Son of God.

All of these elements, while often used quite differently in the differing Gospels, heighten our awareness of the struggle going on here, between Jesus and the world that, as John puts it, "knew him not."

The personification of the characters that surround him, the descriptions of their personalities and their desires encourages us, the readers, to participate in the drama by constantly asking ourselves the question: "Where would I have stood had I been one of these players in this drama of the trial and crucifixion of Jesus?"

Perhaps we can see ourselves as being among those who welcomed him into Jerusalem as a hero. But would we be able to see ourselves as Peter, denying him? As Judas, betraying Him? Or as Pilate, either wishing to avoid the issue altogether, as in John's account, or washing his hands of the whole thing, so he might appear blameless, as in Matthew's?

Or could we see ourselves abandoning him, as all the disciples did in three accounts, or staying at the foot of his cross until the end, as did the beloved disciple and Mary in the Fourth Gospel? Or, most telling of all, would we see ourselves, could we see ourselves, as being like the religious leaders who condemned him?

Perhaps not; but we certainly don't want anyone coming around to us individually, say, here on OS, telling us we've got our religion all wrong; haven't got a clue what God expects of us; have no compassion for the poor and have indulged our own personal gluttony in the face of God's commandment to love others! I would think our feathers would get just a bit ruffled if someone accused us of that. But that is exactly what Jesus did, isn't it?

Just so, there were many real life factors that colored the writing of the Gospels, which, as we learned last week, were all written about 30 to 70 years after the death of Jesus. The memory of what happened at Jesus' death was deeply affected by the life situations of the local Christian communities in which the Gospel writers lived; and each was a little different. Each Gospel, for example, reflects how the writers perceived the Romans and the Jews.

Take the Romans, for instance. How do you get a balanced portrayal of Jesus when writing in a nation occupied by Romans? How do you offset the negative attitude toward Jesus exhibited by Tacitus, the great Roman writer, who treats Jesus as a despicable criminal; worthy of no more than a few lines in his writing?

How would you overcome Tacitus' portrayal? What if, say, you were to portray Pilate as being a spokesman for Jesus, or at least, not against him? Two of the Gospel writers did just that. If you carefully move through the Gospels according to when they were written: Mark first, then Luke, then Matthew, and finally, John.

Yyou'll see that Pilate is increasingly portrayed as a fair judge who recognized Jesus as innocent of political ambition. This viewpoint not only rehabilitates Pilate in the eyes of Christian readers, but also rehabilitates Jesus in the eyes of Romans: if a Roman Governor of Pilate's stature saw nothing wrong in Jesus, Tacitus must have been mistaken about Jesus being nothing more than a common criminal.

Lets look at just one more example: "How would you characterize Jewish involvement in Jesus' death? Who was involved, responsible, for the death of Jesus? Was it "the Jews?" If so, was it all of the Jews? Or just the Pharisees? The Priests? All the Priests? The Sanhedrin?

What about Joseph of Aramethea, a Jew? Wasn't he in the Sanhedrin? Weren't, in fact, all of Jesus' named followers and the vast majority of all the other followers of Jesus also Jews? Wasn't, after all, Jesus a Jewish Rabbi? So just who are these "Jews" who "killed Jesus?"

Well, it depends on which Gospel you read. If you wish to go easy on the Jewish involvement, or want to limit it to a handful of leaders, read Luke. In Luke there is no calling for witnesses against Jesus and there is no Jewish death sentence against Him. In fact, there is no formal night time trial, complete with the high priest Ciaphas in charge, as in Mark and Matthew. There is only a simple questioning in the morning by the Sanhedrin.

John, who is hard on the Jews elsewhere in his Gospel, also does not write that any Jews were heavily involved in deciding Jesus' fate. John records no Sanhedrin session at all after Jesus' arrest, but only a police interrogation conducted by a different high priest, Annas.

Confused? Add further confusion: John includes Roman soldiers and their Tribune at the arrest, the others do not. This is important, because no Roman Tribune could have been dispatched without the knowledge of Pilate, which would mean that Pilate was involved far earlier and more deeply than any of the other Gospels report.

On the other hand, if you suspect that it was "all of the Jews" who accused Jesus then Matthew's Gospel leads you that way; while Mark and Luke limit their accusations to the Jewish leadership, specifically the priests and the Sanhedrin. John goes easy on the Jewish leaders during the trial period because John believes that the "world" rejected Jesus and so places blame implicitly on everybody, and does not go easy on either the Romans or the Jews as groups. Both are guilty in John's eyes.

We could spend several weeks looking at, and comparing, the Gospel accounts of such things as those above, and things like: How did Jesus view His own death? How did the disciples react at Gesthemene? What did they do at the arrest? Could the Jewish trial even have happened according to Jewish law? What happened at the actual time of death? Did the curtain in the Temple split? Were graves opened? And, later, were there guards at the tomb? And on and on.

But we really don't have time for all that. And, more importantly, if we took the time, would we find out anything that would help us better understand Jesus? Well, I have done that for decades, and can tell you that studying and arguing about such questions does almost nothing to help us learn about Jesus.

What will help us know more about Jesus is to know that each individual portrayal of Jesus' death gives us an insight into who he is such as none of the others give us.

And the reason is simple enough. Each divinely inspired evangelist knows a different facet of Jesus and his Passion, and he portrays, therefore, a different picture.

What I'm going to do now is give you a brief summary of what careful study of three of the portrayals of Jesus and the events leading to his death can tell us. We will look at Mark, Luke and John. Matthew's portrayal of Jesus is closely based on Mark's, and while Matthew adds many details about events, a discussion of Matthew's portrayal of Jesus would be covering essentially the same ground as the discussion of Mark's portrayal.

Mark:

Both Mark and Matthew portray a very human, very vulnerable Jesus. Mark portrays a scene of stark human abandonment of Jesus at the time of his Passion. Yet, in the end God turns it all around, and neither the abandonment of the disciples nor Jesus' own questioning of God affects God's moment of supreme grace in raising Jesus from the grave.

Mark's gospel intends to shock. And it does. In Mark, long before the Passion the disciples were almost universally clueless as to whom Jesus really was, and, even when they came close to the truth they could not accept the idea of a dying Messiah. And it only gets worse as the tension mounts toward betrayal and death.

In the garden at Gethsemene they fall asleep, not once, but three times. Judas betrays him, but Peter is hardly better, denying that he ever knew him. All flee, one in such haste that he leaves his clothes behind, literally saving his own skin - the very opposite of leaving all things to follow Jesus.

The Roman and Jewish judges are seen by Mark as great cynics. Jesus hangs from the cross for six hours, and three of those hours are filled with mockery and three with utter darkness. And Jesus deeply feels abandonment, even by his heavenly Father. Mark's very human Jesus cries but one thing from the cross, quoting the 22nd Psalm, "My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?"

Yet, in the end, God vindicates his Son. If the trial before the Sanhedrin was to assess his threat to tear down the Temple, God in an act of judgment and vindication, tears the veil of the Temple in two. And an outsider, a hated Roman, is heard to say what no Jew, disciple or priest, could ever figure out: "Truly this was the Son of God." In Mark, only after his death on the Cross is it possible to see that Jesus was no false prophet, but was, indeed, the Son of God.

Luke:

Luke portrays a very different Jesus. And the disciples are shown in a far more sympathetic light. They remain faithful to Him in his trials. And, while they fall asleep while Jesus prays, once, not three times, it is only out of their "sorrow." Even the enemies of Jesus look better in Luke. There are no false witnesses produced at the Jewish trial, and even Pilate acknowledges three times that Jesus is not guilty.

The people are not rabble calling for his death, but rather are grieved over what has been done to him. And, just as they show great concern for him, so too is he less anguished by what will happen to him than by what happens to them. At the arrest he heals the slave's ear and on the road to Calvary he worries about the fate of the women in the coming trials. Further, he forgives those who crucified him and even promises paradise to a thief who merely asks to be remembered, a scene only in Luke's Gospel.

Thus, in Luke, the crucifixion becomes a time of divine forgiveness and care. Jesus dies in tranquility, unlike in Mark, saying simply. "Father, into your hands I commend my spirit."

John:

In stark contrast to either Mark or Luke, John portrays a triumphal Jesus, even in death, a Jesus who long before the passion defiantly announced, "I lay down my life and I take it up again; no one takes it from me!" This Jesus knows, in advance, exactly what is going to happen to him and when, and it will happen as and when he says.

When the Roman soldiers and the Jewish police come to arrest him they fall to the ground powerless. In the garden he does not pray for the cup to pass him; for it was for this moment he was born. He is so self assured that he offends the high priest; and even Pilate feels his power. Jesus has no fear of Pilate. saying, bluntly, "You have no power over me." Nor does anyone carry his cross; this is something he is perfectly able to do for himself. Even his royalty is proclaimed in three languages on the cross and is, in fact, confirmed by Pilate.

Totally unlike the three other Gospels, Jesus does not die on the cross abandoned, but with his mother and the beloved disciple with him. And speaking to them from the Cross he gives the beloved disciple and his mother to one another, creating, as it were, a family of loving disciples to carry forward the message.

This Jesus can not cry out "Why have you forsaken me?" because the Father has always been with him, literally "in" him, and will be so through death to resurrection and glorious ascension. His last words bear no anxiety or pain, but the simple statement that he has done what he came to do: "It is finished." And only then, when he declared that he has done what was needed, does he hand over his spirit to the Father.

Even in death he continues to dispense life as living water and blood flow from his pierced side. And his burial is not something hurried and unprepared as in the other Gospels, but he lies in state amidst 100 pounds of spices - as befits a king.

In the final two posts in this series we will go into this in more detail. But let me ask you: do you despair because these portraits are so starkly different? Do you think that one is, must be, more correct? Remember, all three descriptions are given to us by one Holy Spirit, the one Spirit that inspired the writers of each Gospel.

And, understand this well, no one Gospel, or all four Gospels combined, exhaust the meaning of Jesus! In fact, a true picture of Jesus can only just begin to emerge because we have at least four differing depictions.

Why, then, is this Good News? Because by having these differing descriptions people with different spiritual needs can find meaning in the cross. And even the same person, at different points in his or her life, can find meaning there.

As Jesus did in Mark's Gospel, have you never needed desperately to cry out "My God, My God Why Have You Forsaken Me?" Have you never felt that? Do you not need to know that when you feel that way, just as Jesus did, God has not abandoned you and that he can reverse tragedy in your life?

As in Luke's Gospel, have you never been hurt by others, deeply hurt, and have finally found some relief from your anger in forgiveness? Is "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do" not something that we need to hear, knowing that our Savior had far more reason to hate than we shall ever have?

Don't we, with Luke's Jesus, need from time to time to turn ourselves over fully to God, having been unable to fix things for ourselves? Can we not find hope and comfort in saying, "Into your hands, O God, I place myself."?

Yet, as in John's Gospel, are there not times in your life when you desperately need to know that evil and sin and all the perfidy of this life cannot prevail against God and those who have faith in him?

With John don't we often need to believe that we worship an all knowing, fully in control, always in command, Jesus who will guide and protect, defend and defeat every foe and evil, be it the prevailing powers, or the principalities or the purveyors of lies?

Jesus is all of these and more, far more than can ever be captured by putting pen to paper. These descriptions do not exhaust the portrayal of Jesus, they begin the task. Each Christian will ultimately find a portrayal of Jesus the Christ that fits his or her personal needs. And that portrayal will not be complete for everybody else, and may change over time as we learn more about the One in whom we place out trust.

Hopefully this brief Lenten series has begun to outline for you some of the major characteristics of Christ that will give you a basis for a better understanding of the One whom Christians call "Our Lord and Savior."

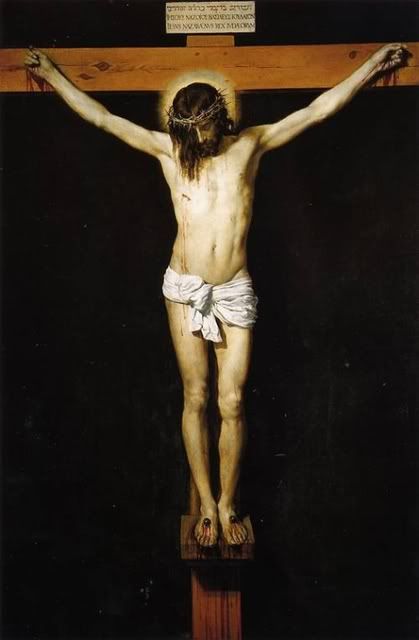

Listen to Fr. Raymond Brown. "To choose one portrayal of the crucified Jesus in a manner that would exclude the other portrayals or to harmonize all the Gospel portrayals into one would deprive the cross of much of its meaning. It is important that some be able to see the head bowed in dejection, while others observe the arms outstretched in forgiveness, and still others perceive in the title on the cross the proclamation of a reigning king."

That, my friends, is Good News.

Monte

Original posting, 1400 page views before counter was removed

This posting for 2010: