Christian liturgy, ritual and most of Christian theology change little from year to year. The reason for the Christian Calendar is to encourage Christians to rehearse, ponder and reflect on, year after year, the life, death and resurrection of Jesus, the Christ, so that His life becomes part and parcel of our family history.

The story of Christ changes little, but we, His disciple, change and grow, become ill, or face death, our own or a loved one's, and in so doing we come each year to view the events of Christ and the traditions of His Church through different eyes.

Hopefully, what I write in this series will have a certain timelessness, updated slightly each year to improve clarity and thereby open more deeply our understanding of aspects of the events celebrated during the Christian Year.

This Lenten essay for 2010 lays out some basic parameters of orthodox Christian belief. What is written here are my own beliefs, which are widely shared by Christians in most mainline Protestant denominations and in the Roman and Orthodox Catholic denominations in the United States as being fundamental to Christian faith.

Note: Links to the first three posts in this Lenten series can be found in the left column of this page under the MY LINKS, The Christian Calendar Series.

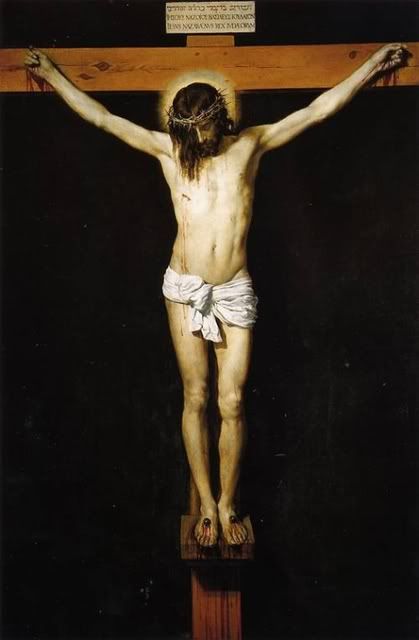

Jesus: "Caring, Compassionate and Concerned"

Overview:

In Part One I introduced this series on The Death of the Messiah. I pointed out that, while we may think there is only one story of the death of the Messiah, repeated four times, in fact there are four different renditions of the story of Jesus' death, both in the details and in the portrait of Jesus presented. I also said that there is also a fifth rendition: the one that we create from the other four.

I explained that I believe that these Gospel stories were divinely inspired and God was therefore both mindful of the inconsistencies in the stories, and intentional in his/her inspiration, in that God wants us to be able to see Jesus' death from four unique vantage points.

Therefore, we do not improve on the Gospel accounts by trying to harmonize them, regardless how tempting it is to try to do so. Ultimately, all attempts at harmonizing the Gospels fail and never give a true picture of what God is saying to us in those sacred texts.

This fact, however, gives ulcers to many who believe that the stories of Jesus must all be clear, concise, neat and without factual disagreement.

Part of the problem for such people is that they insist on viewing the Gospels as history, which they are not. They are theology told in narratives, stories, and are kerygma, proclamation of the Good News of Jesus the Christ.

In Part Two, using two major examples of the differences in three of the Gospel accounts of the Death of the Messiah, we explored my contention that it is good to have four differing Gospel accounts.

Having four different depictions of both the narratives of the stories and then seeing how Jesus reacts to essentially the same events allows us to see that Jesus is a far more complex character than the portrait we often hold of him.

In Part Three we looked in some detail at Mark's Gospel portrayal of Jesus and of the events leading up to his Crucifixion.

Mark, the earliest Gospel written, portrays a very human, very vulnerable Jesus. His portrayal of Jesus, the disciples, and all of the actors in this drama of death, shows people in all of their human frailty, in their evil plotting and their despicable actions. In the end, Mark shows that we all, even Jesus, have no choice but to depend on God.

Today, with Part Four, we finish this series of Lenten Reflections looking at the very different portrayal of Jesus and the events leading to his crucifixion in the Gospel according to Luke.

Luke wants us to see a Jesus who is at once aware of his approaching death, but also who clearly worries about others far more than he worries about his own fate. Luke's Jesus is "Caring, Compassionate and Concerned" about others.

Just as we have not looked at Matthew because its basic portrayal of Jesus is similar to Mark's, so too we will not look at John because it is so very different than the three "synoptic" Gospel accounts (Mark, Luke and Matthew), that it would take a whole new series to explain it.

Thus, as we now come to the end of this series, we have learned that each of the four Gospel accounts paint a part of Jesus that appeals to different people, and even to the same person at different stages in his or her life.

The genius of the Gospel accounts of the Death of the Messiah is not that they agree in the details but rather in that they give four different, yet surprisingly clear, portraits of the Messiah that help to broaden our understanding of him.

Luke clearly relies heavily on Mark, but many of the details are different. While Luke shares another common written source with Matthew, called simply "Q," Luke also clearly has his own sources of information which have been handed down by eyewitnesses and others over the decades since the crucifixion. These sources were unknown to Mark.

Molding at least three sources into a coherent Gospel is clearly a task of great importance to Luke. He tells us in the opening of his Gospel that he desires to "write an orderly account" of the events of Jesus' life, that we might know the truth concerning the good news of Jesus Christ. Luke makes it clear right at the beginning that he is writing theology, not history.

And it is clear when reading Luke and comparing his account of the Death of the Messiah with the other gospels that Luke has a different theological agenda than any of the other three.

Luke wants us to see a Christ who is at once aware of his approaching death, but also a Christ who clearly worries about others far more than he worries about his own fate.

In order to really understand Luke's portrait of Jesus' death it is necessary for us to remember that Luke is a consistent writer. He wrote not only his Gospel account of Jesus but also the only deliberate account of the very early church, which we know as the Book of the Acts of the Apostles. The Book of Acts flows seamlessly from the final scenes of the Resurrection at the end of his Gospel.

Nothing about Luke's reporting of the Death of the Messiah is inconsistent with what he has told us about Jesus, his disciples, and the Christian community as reported in both his Gospel and in his Acts of the Apostles.

Thus, in Luke, the Jesus who is accused by the Jewish leaders of "perverting our nation" is the same Jesus whose infancy and upbringing was in total fidelity to the Law of Moses. The Jesus who is accused of "forbidding us to give tribute to Caesar" is the Jesus who has declared the opposite, to "render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's".

These, and other incidents in his life prior to his arrest, highlight a major theme in Luke's description of the Passion: that Jesus is totally misunderstood by all authorities, is innocent and is unjustly accused and killed.

Likewise, the Jesus who shows such great concern and compassion for others during his Passion is the same Jesus who is already compassionate; showing concern for the widow of Nain and praising in parables the mercy shown by the father to the prodigal son and to the man beset by thieves on the way to Jericho, in the story we call the "Good Samaritan."

Thus, we should not be surprised by the Jesus who shows forgiveness toward those who crucified him.

When we are told by Luke that, after the Temptation, Satan leaves Jesus, "until an opportune time," we should not be surprised that Luke writes that Satan returns to inhabit Judas, his betrayer at the end of Jesus' life.

In Luke it is much more than personal greed and sin that motivates Judas, it is the work of the Devil himself. Luke is so clear about this that one could argue that Judas was innocent of any sin, because, literally, "the devil made him do it."

Unlike Mark, who emphasizes the dullness and failures of the disciples, Luke finds them attentive and trying to learn, if stumbling from time to time. Luke, for example, never mentions that the disciples fled at the time of trial. In fact, while not at the cross itself, Luke places them, with the women, waiting and watching in the distance.

Nor will they flee after his death and head for home in Galilee as in the other Gospels, but they will await his return in Jerusalem, where Jesus will appear as the Risen Christ. And later, apostles who are derided in Mark and Matthew will appear as major Christian leaders in the Book of Acts.

Even the way Jesus behaves during his passion will set the example for how others will behave in the future, as first Stephen, and later Paul, endure the same cast of adversaries and will respond in the same way when their time comes to bear their crosses. Luke clearly shows this in the Book of Acts.

Therefore, there is a smooth consistency in doing the will of God throughout Jesus' life, death and resurrection, and, ultimately, even by the early Church after Jesus has ascended to God. This consistency in showing the achieving of God's purposes, first through Jesus and then through the Church, is a major theme in Luke's work.

Looking at the Passion itself we see that the scene of prayer and arrest at Gesthemene as described in Luke is far less dramatic and suspenseful when it comes to the actions of the disciples. No words of rebuke are spoken to them.

In fact, just the opposite, for at the Last Supper Jesus has already told them, "You are those who continued with me in my trials." And Jesus has already assured them of a leadership place in Heaven, including responsibilities for judgment of the twelve tribes of Israel.

Therefore, we can not imagine that the disciples will fall away at this late date; and they do not. Even at Gesthemene he does not separate Himself far from them, going only "a stone's throw away" to pray.

Luke describes them as sleeping while Jesus prays, but not falling asleep three times after being admonished to stay awake. Rather they sleep but once, and then only "out of sorrow."

And, when Jesus finds them sleeping he does not harshly rebuke them but shows his concern for them, telling them to get up and pray that they may not come into their own time of trial.

Thus, the drama of the scene focuses not on disloyal or cowardly disciples but on the actions of Jesus, which are caring and compassionate, and thus quite different than those described in Mark.

Unlike in Mark, this Jesus is not one whose soul is sorrowful unto death. Rather, on his knees he prays in subordination to the will of the Father. And, in Luke, that prayer does not go unanswered, for the Father sends an angel to give him strength.

This brings what has been translated into English as "agony" or "anguish" and great drops of sweat like blood fall from him. But for centuries Christians have greatly misinterpreted this dramatic scene because of poorly translating the Greek word, "agonia."

It means the great preparatory tension of an athlete warming up for a great contest. It does not mean fear or pain, as it is often misinterpreted. The angel has given him strength, not weakness.

And, at the arrest, Jesus is very calm; a calmness that bespeaks a foreknowledge on the part of Jesus of what is going to happen. He addresses Judas by name and is in no way surprised to find him here betraying him.

When the slave's ear is cut off by one of the disciples, Jesus, again showing compassion, heals him, and tells the disciples, "No more of this!" As he has shown compassion to his enemies throughout his ministry, so he shows compassion here.

Jesus knows exactly what is happening and, having been strengthened by the angel, is intent on carrying out what he knows to be the will of the Father.

The struggle is great but Jesus is up to the task. The Devil himself occupies Judas, and no underlings come alone to arrest him as in Mark, but rather the chief priests and elders themselves lead the Temple police.

Jesus knows the evil in this, telling them that this is "their" hour, a time of the power of darkness. Yet he also knows that he will overcome it.

As in Mark they arrest Jesus at night. But they take him not to the Chambers of the Sanhedrin but to the High Priest's house, or perhaps the courtyard of that house. (The Greek wording is ambiguous.)

In any case, Luke does not identify to which High Priest the house belonged. Nor is there any Sanhedrin trial that night as in Mark, but rather they hold him there, beating him and mocking him, but not asking him any significant questions.

For Luke the highlight of the evening focuses on Peter who has followed him and, as in Mark, denies him three times. Unlike Mark, however, Luke adds a poignant note: "The Lord turned and looked at Peter." Thus Jesus here makes eye contact with Peter, and it was then that Peter remembered Jesus' prediction and felt the shame of his betrayal.

This dramatic look is found only in Luke, and is symbolic of Jesus' continuing care for Peter, as he promised the disciples at the Last Supper. They may deny him but he will always be there for them.

When it is day they lead him to the Sanhedrin Council Chambers and question him. Unlike in Mark, Jesus answers ambiguously, but they read enough into his replies to decide to bring him before Pilate.

Unlike in Mark and Matthew, there is no formal Sanhedrin trial; it is simply an interrogation. There are no witnesses called, false or otherwise, and there are no condemnations issued by the Sanhedrin. All they say is that they have heard enough to take him to Pilate.

Here the Sanhedrin acts as prosecutor and inquisitor, not as judge. In Luke there is but one trial and that is before Pilate.

Through it all Jesus is calm and self-composed. He is not like the majestically supreme Jesus portrayed in John's gospel, but rather he exhibits the serenity of one secure in the knowledge that God is in charge, and he is content in the knowledge that he is wholly innocent.

He is prepared to go to his death, if necessary, knowing that he has an unbreakable union with the Father.

Luke gives us many more details of the trial before Pilate than do Mark and Matthew. The chief priests and scribes make more numerous accusations against Jesus than in the other synoptic Gospels, including both religious and political claims.

And, as Luke describes in Acts, Paul will later encounter an almost identical sequence of actors, issues and events in his trials. Thus, an important point is made in Luke: the tone for the bearing of later Christian crosses by faithful disciples is set by Jesus here.

Pilate comes off well in Luke, even if he is ultimately weak, finally giving in to the demands of the crowd, led here by the chief priests and other Jewish leaders. Initially, having heard their complaints, Pilate tells them that he has examined the charges against Jesus and that he finds Jesus guilty of none of them.

Then, hearing that Jesus is a Galilean, he sends Jesus off to Herod, Tetrarch of Galilee, who is in town for the Passover. This sidebar is only present in Luke.

Herod, oddly, is glad to see Jesus because he has heard of him and wants to see some "sign" from him. Jesus does not oblige; and while the chief priests continue to accuse him before Herod, just as they had before Pilate, Herod finds, as did Pilate, nothing against Jesus.

But Herod is miffed at Jesus' silence, so he mocks Jesus by placing an elegant robe on him, and then returns him to Pilate.

Luke tells us that, ironically, from that day forward Pilate and Herod, heretofore enemies, became friends. Thus, even while under such great duress Jesus is seen to be able to influence the healing of relationships, simply by his presence, even between those who mistreat him.

It is in this final series of scenes of the Death of the Messiah where Luke's account is even more radically different than any of the other three Gospel accounts.

Once again Pilate examines the charges against Jesus, and, once again, tells the Jewish leaders that neither he nor Herod find Jesus guilty of any of the charges. And Pilate boldly tells them that "Indeed, he has done nothing to deserve death." Pilate then proposes to have Jesus flogged and released.

All of the accusers, not just the crowd as in Mark, but the chief priests, other Jewish leaders and the people, shout to do away with Jesus and to release Barabbas.

Luke tells us that Pilate, wanting to release Jesus, addresses them a second and third time, telling them Jesus is not guilty. However, Luke then tells us that Pilate caves in to the accusers, and "their voices prevailed."

Because Luke contains no scene in Pilate's courtyard of Roman soldiers beating and mocking Jesus, the implication in Luke is that Pilate handed over Jesus to the Jewish leaders who take him to Calvary and crucify him.

Later, however, we hear that soldiers along with the leaders also mocked him while he was on the Cross. So, regardless who led Jesus to Golgatha, Roman soldiers were present at his death.

What is far more clear, and clearly different than Mark and Matthew, is that the people who followed Jesus to his crucifixion included a great many who were not hostile to him, particularly women, who were lamenting what was happening to him by beating their breasts and wailing over his fate.

To these Jesus shows great compassion, warning these "daughters of Jerusalem" of the coming trials, telling them not to weep for him, but for themselves.

[Note: This scene is likely influenced by Luke's anachronistic knowledge that Jerusalem was destroyed in the period 68-70 AD when the Romans quelled a Jewish rebellion. At that time many innocents, women and children, were killed, and many Christians fled the persecution in the city. Luke already knew of that event when wrote his Gospel.]

Regardless, Jesus remains calm and concerned for others. Unlike in Mark, the first words uttered by Jesus from the cross are not of his feared abandonment, but rather, "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do."

There is a strong implication here that the Jewish leaders acted out of ignorance, not with deliberate evil and viciousness, as in the other New Testament traditions. Clearly, as Luke describes them, they were ignorant of who Jesus was and this shows how far Jesus is willing to go to find forgiveness of his enemies.

This is a far more humane treatment of the Jewish leaders than in the other Gospels, and is a clear directive to later Christians to be gracious toward, and forgiving of, our worst enemies; something that most find nearly impossible to imagine let alone to do.

In Acts, Stephen will find strength and hope in repeating Jesus' thoughts, praying as he died under their stones, "Lord, do not hold this sin against them."

And still later, thousands of Christian martyrs will go to their death finding courage in these words from the Cross.

In another major departure from Mark and Matthew, both criminals do not mock him from their crosses. Rather, one of the two thieves acknowledges his own guilt and confesses the innocence of Jesus.

This "good thief" as we often call him, asks to be remembered by Jesus when he comes into his kingdom. And, still filled with compassion, Jesus does him far better than that, promising him that he will be with Jesus in Paradise yet that day.

Many have said that, because of the compassion of Luke's Christ, the "good thief," who offered no confession of his sin nor made any profession of faith, literally stole the keys to the Kingdom. That old saw is not far from the truth.

In the last, dark, hours of Jesus life he does not lose confidence. He does not, as in Mark and Matthew, feel abandoned by the Father. Rather he is calm and at peace, secure in his knowledge of the goodness and justice of the Father.

There is no agony recorded, only the confident giving of his life over to the Father, even as he has given his life to others throughout his ministry. Jesus dies saying, "Father, into your hands I commend my spirit."

Just as the words of forgiveness have given many a martyr courage in their own deaths, so to have these words of confident trust in God given hope not only to martyrs but also to many ordinary Christians at the time of their death.

Luke, unlike the other writers, places the tearing of the curtain of the Temple in two before the death of Jesus. After his death Luke will record only acts of heavenly grace, not justice or retribution.

And, if the innocence of Jesus has not been clear enough for all who read Luke, at the foot of the cross the Roman Centurion says not that Jesus was the Son of God, but that he was "innocent."

Even the crowds who watched share the feeling of Jesus' innocence , returning to their homes in great distress, beating their breasts.

It is not necessary for the Centurian to say the Jesus is the Son of God. By this point in Luke's Gospel we are well aware that Jesus is the Son of God.

Standing at a distance are not only the women, but all of Jesus friends who had followed him from Galilee, including, of course, the disciples, who have not had the courage to go to the foot of the cross, but who clearly have not totally abandoned him as they do in Mark's rendition.

Likewise, Luke clarifies the role of Joseph of Aramathea, saying that he had not agreed to the Sanhedrin's plans. Joseph takes the body and lays it in a fresh tomb. And Luke tells us that the women went home to prepare spices and ointments for his body.

After the Sabbath Luke tells us that they came to the tomb with their preparations, only to find the tomb empty. Later, Peter, who has not gone to ground in Galilee, but who has stayed in Jerusalem, will run to the empty tomb and be amazed by what he sees.

Still later, Luke tells us that the Risen Lord appeared to Peter, thus confirming the truth of Luke's message: Jesus will be with and watch over all of his disciples and followers, even those, who, like Peter, deny him in periods of weakness.

There should be much consolation in that fact for us Christians, because most of us falter in periods of weakness and doubt. But Christ is here for us and will watch over us. He will never abandon us regardless of the strength of our faith at any given moment.

And so ends this exploration of The Death of the Messiah. Throughout the world Christians now are in the midst of the Lenten Season.

It continues to be my hope that this brief series has been a help to those who want to understand the Christ and his Passion at a depth that they may not have known before.

I particularly hope that this series has put to rest some of the nonsense about harmonizing and homogenizing the Passion which is so appealing to many but which totally misses the point of having four different Gospels in the first place.

Just as "God don't make no junk," so too God did not send his Spirit to guide the writers of the four very different Gospel accounts of Jesus by accident. God did this so we may see the at least four different sides of the one we now call The Christ.

And finally, please remember that the Gospels do not pretend to be history books. Writing history as we know it today was not even a known practice at the time the Gospels were written. To apply today's historical research methods to the Gospels is at best a silly exercise.

Those who continue to search for the "Historical Jesus" will forever get their doctorates, their accolades, and sell their books to those who insist that one and only one portrait of Jesus must be "the right one."

But this is the same mind set that stunts our understanding of the four Gospel accounts by insisting on harmonizing the Gospels as if they were simply data sources for creating the "one" "real" story of Jesus.

But the Gospels cannot yield anything approaching an "true" history of Jesus simply because they were never written to be what we think of as history.

They were always theology, theology told in story, in narrative, form. They are now, and always have been, kerygma, proclamation, of the Gospel, the Good News, of Jesus of Nazareth, the Son of God, the Christ. This theology forms the foundation of the Christian faith.

To my Christian readers I offer this hope: that the rest of your Lenten journey may be one of both discovery and peace, secure in your belief that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and our Redeemer and Lord.

Monte

1874 page views 2010 03 26